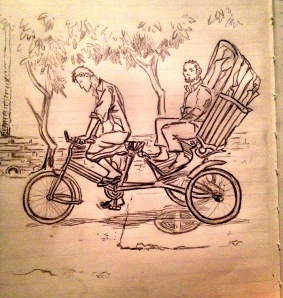

Bicycle rickshaws are everywhere in Dhaka. Brightly-colored, squeaking, grinding contraptions by which thin men with knotted-rope sinews pedal businessmen, school bound children and their burka-clad mothers, tourists, and families of four around the city, operating for short distances and able to reach some streets that larger vehicles can’t fit.

From what I’ve heard and researched, most of these men are here as a result of urban flight, seeking better job opportunities in the big city away from the struggles of eking out a living from the soil. Though Dhaka is known most for its garment factories, transport jobs are low-skilled and perhaps even more readily available. Only a fraction of the bicycle-rickshaw wallahs actually own their vehicles. The majority rent the use of the rickshaw for a few shifts, giving the owner a cut of their earnings, and feeding their families day to day on the remainder.

But are these jobs opportunity for the urban poor or unjust and cruel exploitation?

A year ago, my first time in Kolkata, I was talking about the prevalence of rickshaws in that city with a seasoned NGO worker. “Kolkata,” she said, “mostly uses auto-rickshaws (AKA “CNGs” for: the Compressed Natural Gas which powers them). Bicycle rickshaws were mostly outlawed several years ago. They exist, but we never use them.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Because its horrible!” she said, as if it were the most obvious thing in the world.

And there’s truth to that. These rickshaw wallahs are quite often, if not always, impoverished, overworked, and underpaid, hauling their light vehicles through dangerous traffic and inhaling their city’s toxic smog all day long. They’ll earn only enough to keep them afloat day by day, not enough to save.

But, on the other hand, these men do have work. Inhumane working conditions with little opportunity for advancement yes, but when the alternatives are worse, more dangerous, and pay less, the rickshaw wallah still has the ability to earn a living for the unskilled laborer, however sparse that living may be, and the dignity that comes with that ability.

There’s a section in the novel Shantaram by Gregory David Roberts where Lin, the hero of the tale, is talking about the men in Bombay who run around town with a water cart, manually filling tanks around the city:

“He told me it was a people job… that each man is supporting a family of four from his own wages… They were strong, those guys. They were strong and proud and healthy. They worked hard to earn their way, and they were proud of it. When they ran off into the traffic, with their strong muscles, and getting a few sly looks from some of the Indian girls, I saw that their heads were up and their eyes straight ahead.”

New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristoff takes this idea of the worth of manual work in poor conditions a step further in his 2009 article “Where Sweatshops are a Dream.”[1] Kristoff, writing from years of experience living and reporting from East Asia, controversially argues that sweatshop and manufacturing labor actually ought to increase to help the plight of the urban poor, as the alternatives are far more terrible.

Now all of that doesn’t mean the whole situation is all fine and dandy. Conditions and opportunities for the poor, the disenfranchised, and the disempowered, need drastic change and reform. Fair wages, safety regulations, and revamping or actually enforcing traffic laws would do wonders for rickshaw wallahs and garment factory workers alike, and fair-trade, fair-wage jobs that can actually support and empower individuals absolutely ought to be championed and sought for. But, while that is pursued, I still would rather see a man working as a rickshaw wallah than as a trash picker.

I write that with a bit of trepidation coming from a city like Dhaka, a place that has made the news over the last few years with hundreds dying in unsafe factory collapses or fires, and where the newspapers tell everyday of horrific traffic fatalities. I am by no means blind to the suffering, or the things that we ought to fight to change. But I realize that it’s more complicated than that. We can’t just say – “these working conditions are horrible so we must get rid of them.” Because then, where will the people go?

I think about all of this when I climb on the back of a rattling rickshaw here in Dhaka. I think about the arguments of those who won’t take rickshaws because of the danger and conditions for the workers. But then I think too that, like it or not, right now this is how these men feed their families. So, still not entirely sure of myself, I ride along the weaving, wobbling way, and I stumble through my Bangla phrases and hand over a fistful of Taka at the inflated “Badeshi” price, and I hope that it’s the right thing to do, and not the easy way out.

[1] Nicholas Kristoff. “Where Sweatshops are a Dream” in The New York Times –http://www.nytimes.com/2009/01/15/opinion/15kristof.html?_r=1&hp&version=meter+at+9®ion=FixedCenter&pgtype=&priority=true&module=RegiWall-Regi&action=click – 14 Jan 2009.