The people can get to you. The staggeringly warm hospitality, open homes, hot food, generous smiles and generous portions (“No, no. You must take more.”) In all the places I’ve been in the wide world, the Bengali people I’ve encountered (and Indians) have been some of the most generous and hospitable I’ve ever met. A few folks and I met recently at the house of an Indian couple I’ve had the pleasure of getting to know a bit over the last month, soaking up their wisdom and eating their food. The spread for dinner was absolutely fantastic: lentil stew, dhal, rice with nuts and garnish, fresh vegetables, roti, chicken, fish, and ice cream for dessert. She had spent literally all day cooking for that evening, and that after a long week of visiting and helping an impoverished young woman through the delivery of her first baby. “Yes, it’s very tiring being a mother to so many people,” she said offhandedly. Would a foreigner, only in the country for a few months, be welcomed so warmly, so genuinely in the U.S. I wonder? In my own church? By my own friends and family? They set the bar high.

The Bangla language can get to you.

“Shorkari chuti” means “government holiday.” “Torkari chuti,” while easy to mix up, means “vegetable holiday.” This, as it turns out, does not make sense, but results in a lot of laughter from the Bengali staff.

The sentence structure is completely different from any kind of Western sentence structure I’ve ever seen. It worse my in English writing may make.

“Shobdo” can mean either “word” or “loud.”

Quite often I am unable to remember the Bangla word for “I forget.”

I counted 42 different words specifying the relatives we, in English, would call “Father, mother, grandfather, grandmother, uncle, aunt, niece, and nephew.” Where, in English, we might say “that’s my uncle.” In Bangla there are different words specifying your father’s sister’s husband – and then two different versions, depending on whether a Muslim or Hindu is in question.

I expressed my consternation at this arrangement, declaring that in English there are much fewer words, and it’s much less confusing.

“But then,” begins my teacher, looking genuinely concerned. “If I ask you: ‘Who is that?’ and you say ‘My uncle,’ how will I know if it is your father’s brother or your mother’s brother, or your mother’s sister’s husband?”

I open my mouth, and then shut it again.

The newspapers can get to you. Mixed in with the cricket scores and a beautiful arts page are typeface and ink reminders of just how cheap life comes here, suffering and injustice delivered to your front door for your convenience seven days a week in two languages.

The gritty stories spare no expense on vivid detail. A murder victim found by the railroad tracks, throat cut with a wire. Assistant sub-secretaries of some committee of some political party bound and beaten at a university riot.

Every week it seems I read another story about another rape that ends the same way – the perpetrator gets off with a fine, while the victim, often a young girl, is either forced out her village because of the shame or forced to marry her rapist. She is “tainted” now. “The victim was found hanging by the neck from a scarf, having committed suicide,” the stories end.

But while it’s all raw and real, it’s not just tales of carnage, corruption, and injustice. There’s also the highlights of the people feeding the poor, profiles of local artists capturing beauty in the streets and the beautiful faces of a beautiful people, rags to riches stories and poetry reviews and calls for reasonable dialogue.

That’s when the beauty can get to you. The wonder. Unexpected. Takes you by surprise.

I was at the gym lifting weights, a daily ritual that keeps me sane and sleeping well with the physical challenge and exhaustion, when outside the rain came pouring down like a sudden flood into an ash bin.

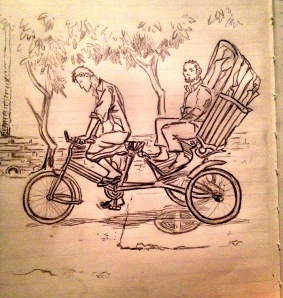

After the storm I walk back as the sun is setting, and the light seems trapped, pressed down under the swollen honey clouds. Rays ricochet between the skyscrapers and the puddles ‘til it seems the very atmosphere is glowing. A creaking rickshaw wheel dashes the light from a puddle in front of me, and then I wait and watch as the water settles and the picture reforms: a clear, still, honey-gold reflection of the trees overhanging the road. For a few moments, before the all that glow escapes out of the gray, there’s poetry on this road, in this city – and its very elusiveness, its very transience, makes it worth the chase.